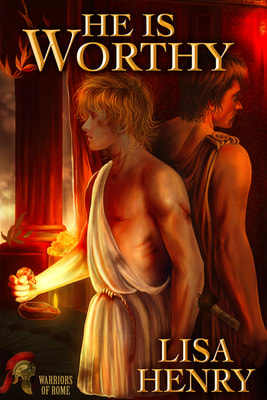

Cover art by Petite-Madame VonApple.

Cover art by Petite-Madame VonApple.

Rome, 68 A.D. Novius Senna is one of the most feared men in Rome. He’s part of the emperor’s inner circle at a time when being Nero’s friend is almost as dangerous as being his enemy. Senna knows that better men than he have been sacrificed to Nero’s madness—he’s the one who tells them to fall on their swords. He hates what he’s become to keep his family safe. He hates Nero more.

Aenor is a newly-enslaved Bructeri trader, brutalized and humiliated for Nero’s entertainment. He’s homesick and frightened, but not entirely cowed. He’s also exactly what Senna has been looking for: a slave strong enough to help him assassinate Nero.

It’s suicide, but it’s worth it. Senna yearns to rid Rome of a tyrant, and nothing short of death will bring him peace for his crimes. Aenor hungers for revenge, and dying is his only escape from Rome’s tyranny. They have nothing left to lose, except the one thing they never expected to find—each other.

Aenor is a newly-enslaved Bructeri trader, brutalized and humiliated for Nero’s entertainment. He’s homesick and frightened, but not entirely cowed. He’s also exactly what Senna has been looking for: a slave strong enough to help him assassinate Nero.

It’s suicide, but it’s worth it. Senna yearns to rid Rome of a tyrant, and nothing short of death will bring him peace for his crimes. Aenor hungers for revenge, and dying is his only escape from Rome’s tyranny. They have nothing left to lose, except the one thing they never expected to find—each other.

The descriptions are detailed and vivid and make ancient Rome just come to life. It is exciting and fast paced and kept me eagerly turning pages...

- Joyfully Jay

- Joyfully Jay

Reviews of He Is Worthy:

Gay Book Reviews

The Blogger Girls

Joyfully Jay

The Reading Life

La Crimson Femme

The Jeep Diva

Live Your Life, Buy The Book

Sinfully Sexy Book Reviews

Bluebird Books

Padme's Library

Gay Book Reviews

The Blogger Girls

Joyfully Jay

The Reading Life

La Crimson Femme

The Jeep Diva

Live Your Life, Buy The Book

Sinfully Sexy Book Reviews

Bluebird Books

Padme's Library

An except from Lisa Henry's He Is Worthy:

Chapter One

Cenchreae, the port of Corinth, Greece, 67 A.D.

The man had been drinking steadily all afternoon, paying no attention to the other customers in the wine shop, only growling and moving his cloak aside to show the gladius at his belt when another customer jostled him. The man was trouble.

He was also bad for business.

Crito sent the girl over.

“Another drink?” she asked him.

“Keep them coming.” He spoke Greek with a Roman accent.

Romans—gods curse them—were the scourge of world. If there was trouble and this man killed someone or, worse, got himself killed, Crito knew exactly where the blame would fall. A humble Greek wine shop owner wouldn’t get much of a fair hearing in front of the Roman magistrate in Corinth.

Crito muttered to himself and sent the girl into the back room for another jug of wine.

The Roman’s money was good. That was the only reason Crito was letting him stay. That, and the gladius. Military issue, probably. The last thing Crito needed was to make a trained legionary angry. Tonight, of all nights. The streets were already wild. Such an upheaval!

Corbulo. Dead.

Was the death of a true Roman hero in Cenchreae good for trade or bad for trade or, in the long run, did trade not care? Maybe for the next few years, people would point at the spot where the great man had disembarked—great, Crito allowed, for all that he was a Roman—and received the imperial messenger with Stoic virtue. But sooner or later, it would be lost in the comings and goings of thousands of ships, the bustle of commerce, and the eternal rhythm of the tides. First nobody would care, and then nobody would remember that the general who’d brought the Parthians to their knees and restored Armenia to Rome had fallen on his sword in humble Cenchreae.

A sudden gust of wind blew the shutters closed. The Roman scowled at the foul weather. He muttered something. Axios, Crito thought, but wasn’t close enough to be sure. He is worthy. It made no sense, and Crito chalked it up to the language barrier.

The girl brought the man another jug of wine and said something to him in a low voice. He patted the stool next to him, and she sat down.

Crito leaned on the counter and caught the eye of a potter leaning on the other side.

“I was at the docks,” the potter said.

“Did you see Corbulo?” Crito shivered. “Did you see what happened?”

The potter’s shoulders slumped. “I’ll tell you what happened, friend. Nobody’s buying, that’s what fucking happened.”

Crito nodded.

A group of men entered the wine shop, their cloaks fluttering around them in the wind, their hair on end. Crito cut short his chat with the potter, shot the girl a filthy look—she was nodding and murmuring at something the Roman had said—and greeted his newest customers with a forced smile.

“It seemed like most of Greece turned out to meet Corbulo,” one of the traders said. He was a tall, sallow man with a crooked nose. His accent was Alexandrian.

His companions nodded and murmured in agreement.

Corbulo’s name was being spoken like an invocation in Cenchreae tonight. Crito wondered if the man himself could hear the murmur of countless voices or if he had already crossed the black Lethe and sunk into forgetfulness.

Outside, the wind bustled up and down the streets and rattled the doors and shutters. There had been children with strings of flowers heading for the port in the morning, to welcome Corbulo and his entourage to Greece. And now the hero of the empire was dead by his own hand. Unthinkable.

Crito looked at the Roman sitting with the girl and wondered about the gladius. No, if the man was a legionary from Corinth sent to quell trouble—or cause it, who knew?—he would not be drinking alone in a wine shop by the docks. Crito wished he’d chosen somewhere else.

“Any man can make war, but only a great man can make peace,” the Alexandrian trader announced. “Corbulo was the best of his generation!”

A crash from the far side of the room signaled the Roman’s attempt to stand. The stool had fallen backward as the man rose to his unsteady feet. He gestured to the girl, knocking the wine jug with his forearm. It smashed onto the floor.

The Roman swayed. His gaze found Crito’s and he pulled a handful of coins out of the leather pouch on his belt. He rained them down onto the table.

“That’s for the wine. That’s for the jug.”

Crito gaped. Those were silver coins the Roman was throwing around.

The Roman blinked at them. “And that’s for the stool.”

Crito moved out from behind the counter. “The stool, sir? The stool is fine.”

The girl hurried toward him. “Master, shhh! Let him. Let him.”

Let him? Let him what? Crito gasped as the Roman turned, stooped to pick up the stool, and swung it. He roared, and the stool shattered against the wall.

The Roman stood panting.

“No, no, no,” Crito babbled in the sudden silence, looking anxiously toward his other customers. “No, you must go outside, please.”

“Get me another drink,” the Roman said. He sat back at the table on the girl’s stool.

“Master,” the girl said, pulling Crito away by the wrist. “Do as he says.”

Crito looked at her, looked at the Roman, looked at the smashed stool and looked at the coins.

“You can serve him,” he growled, “as long as he keeps paying.”

“His money is good, master,” the girl said. “His goodwill is better.”

Crito snorted. He hadn’t seen much in the way of goodwill from the Roman so far. “Why is he so special? Didn’t you hear?” He raised his voice without intending to. “The only important man to step foot in Cenchreae today was Corbulo, and we killed him!”

The color drained from the girl’s face.

“You didn’t kill Corbulo,” the Roman said suddenly. His mouth quirked up in a bitter smile. “I did.”

“Y-you did?” Crito didn’t dare look at his other customers. They were all frozen to the spot.

A young man, Crito thought wildly. The Roman was a young man. He should have spotted it sooner. Despite the nondescript cloak and the standard military-issue gladius, the Roman was too young to be an ex-legionary, and a soldier on leave wouldn’t drink alone. His accent wasn’t just Roman, it was patrician. Crito should have recognized it sooner. The girl--clever girl!—had picked it up. This was a man Crito did not want to offend.

“I did,” the Roman said. “With nine little words.”

The girl was the only one unafraid to move. She placed a cup of wine on the Roman’s table.

Crito couldn’t break the man’s gaze. He didn’t want to ask, but the Roman was waiting for it. “Nine words?”

The Roman slid a coin across the table toward the girl. He drank, and wiped his mouth on the back of his hand. “He knew me. Ushered his daughter toward me. Mentioned my father’s name.”

Cold dread leeched into the pit of Crito’s gut. No, no, no. He did not want to hear this. He watched as the girl ran a thin hand along the Roman’s forearm and marveled at her audacity.

The Roman drank again. He looked around the wine shop at his captive audience. “Want to know the nine words it takes to kill a hero?”

Nobody spoke.

The Roman’s face cracked with a smile. “You no longer have the friendship of the emperor.”

One of the traders whispered something.

The Roman raised his eyebrows, his face suddenly animated, almost boyish in surprise. “And do you know what he said before he fell on his sword?”

A short, bitter laugh.

Crito stepped forward with a wine jug. His hands trembled as he poured the Roman another cup. “Axios,” he murmured.

He is worthy.

“Axios,” the Roman agreed. His smile faded. He traced his finger through a pool of spilled wine on the table, around the islands of coins, and admitted there, to a group of anonymous strangers in a nondescript wine shop, what Crito doubted he would even admit to himself if he were sober. “Well, maybe Nero’s not fucking worthy. Did anyone ever think of that?”

Chapter Two

The Aventine, Rome, June 68 A.D.

“Up! Up! Up!”

Aenor hauled himself to his feet and squinted into the sudden light. He understood the command, but not the burst of words that followed. Aenor’s Latin was good, he thought it was, but these men spoke too fast. He averted his gaze from the light of the lamp. Filthy twists of hair hung in front of his face.

One of the voices belonged to Ratface. Aenor didn’t know his real name. He was the overseer, thin but sinewy, with a narrow, pinched face and close-set eyes. He carried a whip and was quick to use it.

Aenor didn’t recognize the second voice, and risked a glance.

The man was tall, middle-aged, not handsome, but clean and maybe rich. His tunic was orange and he wore silver rings on his fingers.

“No,” the Clean Man said to Ratface. “I am not a fool.”

Fool? Infant? Aenor had to guess the word from the tone of the man’s voice. His uncle had insisted he learn Latin, and Aenor had thought he had, but there was so much he didn’t know. He knew enough to sell cloth and jewelry to fat wives in Colonia, enough to tell a legionary to fuck off back to Rome, but not enough for this.

Not enough for slavery.

The attack had come out of nowhere. Well, no, not nowhere. Someone had killed a Roman family traveling on the road. An important man, perhaps, and his woman and children. And Aenor and his cousins had laughed, because the man should have paid for better bodyguards, but it wasn’t him and his cousins who had done it. When the legionaries had stopped their carts, they weren’t expecting trouble. A bit of back-and-forth maybe, an insult, a bribe, that was all. They had realized too late to run that this was different. Aenor had been taken and Bana was dead, he’d seen that, but he didn’t know what had happened to the others.

“Filthy Bructeri scum,” the First Spear had said, his greaves covered with blood, and suddenly Aenor wasn’t a free man anymore.

Had it only been weeks? It felt like years he’d been living in this dark cage. He kept his head bowed and listened as Ratface tried to sell him. The dull ache in his stomach, he thought, was the empty place he used to keep his fear.

“I will give you a good price,” Ratface wheedled. Aenor had promised the same thing to those women who’d hummed and hawed over his bolts of woven cloth back in Colonia. “He is—” A sly, teasing word Aenor didn’t know.

The clean, rich man made a clicking noise with his tongue.

“And he will clean up nicely,” Ratface said.

Nicely? Well? Adequately? Aenor stared at his feet.

Aenor had been sold twice since being captured, beginning when the First Spear sold him to the trader for only four hundred denarii. The trader—Aenor had named him Squinteye—had bound Aenor behind his wagon and turned south.

Every sunset and every dawn, every blistering step, every passing moment had pulled Aenor farther away from home. Pulled him into the nightmare he couldn’t escape. The farther south they had traveled, the more different even the air smelled: alien combinations of salt, laurel, and bay trees. Even the dust smelled strange. How would he ever find his way home from here?

Aenor’s first sight of Rome had been a smudge of smoke haze above hills. Too vast to be a city, surely, and his confusion must have shown on his face because Squinteye had laughed and smacked him on the back of the head. Roma. That was Roma.

The road had become wide, busy, and was shadowed for some miles by a massive arched aqueduct. Aenor had seen small farms dotted with goats and sheep. He’d seen huts, ramshackle and packed closer and closer together. Then there were the tombs, some as large and spectacular as palaces, that lined the side of the road. Carved letters that Aenor couldn’t read spelled out the life achievements of the great Romans who reposed inside. All around the tombs, beggars and thieves slipped in and out of the shadows and kept their watchful eyes on the road.

The city itself--sacred Tuisto! Aenor had never seen anything so big, so busy, so loud. Squinteye had left his wagon outside the city with his biggest, most trusted men to guard it, and headed into Rome with Aenor and the rest.

Buildings as high as mountains. Some, Aenor saw, had five or more stories. So many people, so much noise, so much stink. Rome was so big. Too big.

Squinteye had sold him to a fat man who’d brought him to Ratface.

Ratface had put him in a locked cage with four other slaves, none of whom spoke even the rudimentary Latin that Aenor did, in a long, narrow warehouse full of similar cages. Ratface had put a rope around his neck with a tag on it, and threw food into the cage once a day.

As the newest occupant of the cage, Aenor had been given the space closest to the corner they all shat in. The first night, Aenor sat awake, his face buried in his hands, and thought about the goats and sheep he’d seen at the side of the road. Even animals didn’t have to shit where they ate.

By the second night, he was too numb to care.

The days and nights bled together into weeks, and now the Clean Man was here. Aenor told himself he wasn’t afraid, but his skin prickled under the man’s scrutiny, and his guts twisted. He kept his eyes on the ground and forced his trembling fingers straight. Slaves did not make fists.

“It’s a fair price,” Ratface said, “and this one will give you no trouble at all.”

Aenor closed his eyes and tried to imagine he was somewhere else.

The Clean Man clicked his tongue again and sighed. “I suppose he will do,” he said at last. “Send him with the rest.”

When they left, Aenor sank down onto his haunches. He couldn’t stop the acid trickle of fear in his guts. Not afraid, not afraid, but his body didn’t believe it. When he vomited in the corner of the cell, none of the others even looked at him.

*****

Aenor was chained up with five others he didn’t know. They were younger than him, just as filthy. One of them had darker skin than Aenor had ever seen. Rome was so vast, it straddled the world. So much bigger, so much stronger than Aenor had ever imagined when he’d laughed with his cousins back home about what they’d do to the Romans, about how the forest had once swallowed an entire legion. They were Bructeri. They were proud.

They were small. Powerless. Hopeless.

Aenor tried not to whimper as Ratface fastened his chains to the boy in front of him and led them outside.

The sunlight blinded him. Aenor lifted an arm to shield his eyes, and the heavy chains rattled. He walked into the boy in front of him before he realized he’d stopped. They knocked together like skittles, and Ratface laughed.

They walked. Aenor winced at the noise, at the light.

The boy in front of Aenor started to cry. He was small, with skin the color of pitch. He was repeating something over and over, a word Aenor did not know. A god, maybe, or perhaps a parent or a sibling.

No. Don’t.

Aenor watched his feet as he walked, and the feet of the boy in front of him. He stole glimpses of the sunlit world.

A road that crested a hill.

A bottleneck of pedestrian traffic in a large covered marketplace.

A red-roofed building with an arched colonnade.

Plastered walls covered in graffiti and slogans.

A temple.

Aenor stared wide-eyed at a sculpted god, and it stared back at him. The painted orbs of its eyes seemed to see nothing and everything. His head was adorned with garlands of wilting flowers. Aenor didn’t know the Roman gods, but he was afraid of them. He had pleaded with them before.

“Placet,” he had said over and over in the beginning. Please. Please. Please.

The Roman gods were deaf to him, then and now.

“Placet,” he murmured as he passed, but the god in the temple portico stared straight ahead.

Aenor’s muscles ached. The boy in front of him stumbled. Aenor tried to sidestep him, and was pulled back by the length of chain around his neck. He struggled to keep his balance, struggled not to cry out.

In front of him, the boy kept repeating his secret, sacred word.

Tears stung Aenor’s eyes. He wanted to reach out for the boy’s hand, but couldn’t.

Aenor looked up again as they passed through a gate into an arched passageway. A pair of soldiers closed the gate behind them.

“Here’s a fine litter of pups!” one of the soldiers called out, and they laughed.

“Too fine for you!” Ratface returned with a sneer.

After the sunlight and the bustle, it seemed cold and quiet in the passageway. The boy in front of Aenor sobbed as they were led farther into the darkness. Aenor’s guts twisted. What if the boy knew something he didn’t? What if this was the way to the arena? Aenor didn’t want to die for the sport of Romans. He didn’t want to die at all. He just wanted to go home.

Home. The thought was as sharp as a blade, and Aenor flinched.

No. That was never going to happen. He was a slave now. Maybe the Clean Man would be a kind master. Such men existed. Even in Castra Vetera, Aenor had seen fat, pampered slaves. He had heard of slaves who were freed by their masters. He had heard of ex-slaves who were rich. Perhaps being sold to the Clean Man was a good thing. It had to be better than Ratface’s cell.

Ratface led them out into the sunlight again. This time they were surrounded by fine buildings and gardens. Ratface led them toward one of the nearer buildings. A man waited for them at the door. The Clean Man.

The Clean Man glanced at the slaves, and then shook his head at Ratface. “Tell your master I expect better stock next time.”

Ratface sneered. “Tell your master to keep his hair on!”

He began to unchain the slaves.

Aenor kept his gaze down. The Clean Man was a slave. A clean slave. A well-dressed slave. Maybe their new master treated all his slaves so well.

Aenor rolled his shoulders as the weight of the chain slid off him. Hope, uncertain and shy, flared in his chest.

He had seen collared slaves before in Colonia. He had seen tattooed slaves as well, and branded slaves, their master’s initials burned into their faces. The Clean Man bore no marks that Aenor’s quick gaze could find, and wore no collar around his neck. Maybe it didn’t have to be bad. Maybe they wouldn’t make him feel like an animal.

The Clean Man opened the doors of the building, and a cloud of steam billowed out.

Aenor’s eyes widened as the Clean Man ushered them inside. A small group of slaves met them, stripped their ragged clothes from them, and set about them with coarse sponges and buckets of hot water. Aenor closed his eyes, embarrassed at the rivulets of dirty water that ran off his skin. He knelt when the man washing him put pressure on his shoulders. The man dunked his head in a steaming bucket. Aenor yelped at the heat, but the man held him there. When he finally released him, Aenor saw through the dripping tendrils of his hair that the water was now dark gray. He was filthy. He submitted patiently to the rest of the man’s ministrations, sitting quietly while the man took to the planes of his face with a gleaming razor and pumice stone.The man tugged Aenor’s hair over the edge of the razor, the ragged, wet locks dropping to the floor. When the man stepped away, Aenor raised a hand to his bare neck. His hair was shorter than he’d worn it since childhood. It curled around the nape of his neck. It felt strange.

“This one is done,” the man said.

The Clean Man looked him up and down, and clicked his tongue. “Hmmm. We will see. Send him to wait. Check him.”

Aenor, naked, was pushed toward another door.

He shivered.

Too many hands, too many people keeping him moving, too many different faces and places. The man who had washed him shot him a narrow look as they hurried along a passageway. “You understand me?”

“You talk slow, I understand,” Aenor said, anxious to obey.

Trade, he knew. Numbers and orders and prices, he knew. This, whatever this was, he didn’t know, and he was afraid of punishment.

“You follow,” the man said. “You do what I say.”

Aenor nodded.

“In here,” the man said, pulling Aenor into a small room.

Another man was already in there. The master? No. Aenor looked at the frayed hem of his tunic, at the scars across his knuckles. This was not a rich man.

“We check him,” the first man said.

The second man grinned slowly. He said something in an accent too thick for Aenor to understand. Except for that one word.

No. No. No.

The word was close enough. Fuck you! Aenor had screamed in Latin at the legionaries who’d captured him. Tete futue! He knew the obscenity well enough to recognize its conjugation even through the thick accent of the burly slave who was now advancing on him. And, even if he hadn’t, the big man leered and mimed the action.

He was going to be fucked.

No. Tuisto, no.

The big man grabbed him by the shoulders, turned him around, and pushed him down onto the floor. Aenor whimpered and struggled as the man behind him slid a thick finger into the crease of his ass. The second man, the one who had so carefully shaved his face, caught Aenor around the wrists and jerked him roughly forward. The man behind him kicked his legs apart and knelt between them.

Aenor choked on his own sobs. He tried to twist away, and the man behind him growled and reached down to grab his balls.

“You want move?” the man demanded in his strange accent. He tightened his grip. “You want move?”

Aenor whimpered and shook his head.

The man kept a firm grip on Aenor’s balls as his probing finger returned to the crease of his ass. Aenor sucked in a panicked breath as the man’s dry finger breached him. It stung. The man pushed his finger inside Aenor’s passage, muttered something, and pulled it out again.

He used the same word Ratface had to describe Aenor to the Clean Man back at the warehouse. This time, Aenor could hazard a guess: virgin. Ratface’s examination had never been quite so thorough, though.

The big man moved away.

The other man released his grip on Aenor’s wrists. “Up. Get up.”

Aenor, trembling, wasn’t sure his legs would hold him.

“Up!” the man barked.

Aenor struggled to his feet. He backed away from the men into the corner of the room, his gaze fixed on the floor, his hands held in front of his genitals. A shudder ran through him and he squeezed his eyes shut.

There was a place, a secret place that Aenor’s people knew, where the scattered helmets and spears of lost Roman legions moldered in the earth. Aenor had seen it. He had held a helmet in his hands, marveled at the weight of it, and spat on the bones of the man it came from. It was easy to hate Rome in the Teutoburg Forest. It was easy to feel strong.

Not here. Here he was weak. Here he was going to be bent over for Romans, fucked by them.

“And what do we have here?” came a voice from the entranceway. It was a rich man’s voice. A proper Roman accent. The master.

Aenor opened his eyes.

The man wore a long blue tunic shot through with silver threads. He wasn’t tall, but he was handsome. A patrician nose, lips inclined to thinness, and sharp eyes. His neatly cut hair was beginning to turn gray. He wore gold rings on his fingers.

“Do you have Latin?” the master asked him.

Aenor’s voice cracked in his throat. “S-some.”

The burly slave moved quickly. He slapped Aenor’s face. “Dominus.”

Aenor blinked away the sudden tears. “Some, Dominus.”

The master didn’t smile. “What are you?”

“Bructeri, Dominus.”

“German,” the master said. “How old are you?”

His voice shook. “Nineteen, Dominus.”

The master frowned. “Nineteen?” He raised his voice. “Callistus!”

Aenor shrank back.

The Clean Man appeared in the doorway. “Dominus?”

“This one is nineteen!”

The Clean Man gazed at Aenor for a moment. “He doesn’t look it, Dominus. And he’s a virgin.”

The burly slave nodded eagerly in agreement, and Aenor’s face burned.

“I’ll take him,” the master said. “But I expect better in the future.”

“Yes, Dominus,” the Clean Man said.

The master sighed, narrowing his eyes at Aenor. “And make him . . .” He waved his hand. “He’s too old for pretty. Make him look strong. He’s hardly a keeper, but I’m sure he can put on a good show.”

“Yes, Dominus.”

Aenor closed his eyes again.

There was a place . . . a clearing surrounded by trees. A place that still whispered of victory. A place where Aenor had held a Roman helmet in his grasp and laughed as hot blood had coursed through his veins. He was strong in that place.

He searched for it in his memory, invoked it by its secret name, but couldn’t find it. It was lost to him now.

It was Rome’s turn to laugh.

Chapter One

Cenchreae, the port of Corinth, Greece, 67 A.D.

The man had been drinking steadily all afternoon, paying no attention to the other customers in the wine shop, only growling and moving his cloak aside to show the gladius at his belt when another customer jostled him. The man was trouble.

He was also bad for business.

Crito sent the girl over.

“Another drink?” she asked him.

“Keep them coming.” He spoke Greek with a Roman accent.

Romans—gods curse them—were the scourge of world. If there was trouble and this man killed someone or, worse, got himself killed, Crito knew exactly where the blame would fall. A humble Greek wine shop owner wouldn’t get much of a fair hearing in front of the Roman magistrate in Corinth.

Crito muttered to himself and sent the girl into the back room for another jug of wine.

The Roman’s money was good. That was the only reason Crito was letting him stay. That, and the gladius. Military issue, probably. The last thing Crito needed was to make a trained legionary angry. Tonight, of all nights. The streets were already wild. Such an upheaval!

Corbulo. Dead.

Was the death of a true Roman hero in Cenchreae good for trade or bad for trade or, in the long run, did trade not care? Maybe for the next few years, people would point at the spot where the great man had disembarked—great, Crito allowed, for all that he was a Roman—and received the imperial messenger with Stoic virtue. But sooner or later, it would be lost in the comings and goings of thousands of ships, the bustle of commerce, and the eternal rhythm of the tides. First nobody would care, and then nobody would remember that the general who’d brought the Parthians to their knees and restored Armenia to Rome had fallen on his sword in humble Cenchreae.

A sudden gust of wind blew the shutters closed. The Roman scowled at the foul weather. He muttered something. Axios, Crito thought, but wasn’t close enough to be sure. He is worthy. It made no sense, and Crito chalked it up to the language barrier.

The girl brought the man another jug of wine and said something to him in a low voice. He patted the stool next to him, and she sat down.

Crito leaned on the counter and caught the eye of a potter leaning on the other side.

“I was at the docks,” the potter said.

“Did you see Corbulo?” Crito shivered. “Did you see what happened?”

The potter’s shoulders slumped. “I’ll tell you what happened, friend. Nobody’s buying, that’s what fucking happened.”

Crito nodded.

A group of men entered the wine shop, their cloaks fluttering around them in the wind, their hair on end. Crito cut short his chat with the potter, shot the girl a filthy look—she was nodding and murmuring at something the Roman had said—and greeted his newest customers with a forced smile.

“It seemed like most of Greece turned out to meet Corbulo,” one of the traders said. He was a tall, sallow man with a crooked nose. His accent was Alexandrian.

His companions nodded and murmured in agreement.

Corbulo’s name was being spoken like an invocation in Cenchreae tonight. Crito wondered if the man himself could hear the murmur of countless voices or if he had already crossed the black Lethe and sunk into forgetfulness.

Outside, the wind bustled up and down the streets and rattled the doors and shutters. There had been children with strings of flowers heading for the port in the morning, to welcome Corbulo and his entourage to Greece. And now the hero of the empire was dead by his own hand. Unthinkable.

Crito looked at the Roman sitting with the girl and wondered about the gladius. No, if the man was a legionary from Corinth sent to quell trouble—or cause it, who knew?—he would not be drinking alone in a wine shop by the docks. Crito wished he’d chosen somewhere else.

“Any man can make war, but only a great man can make peace,” the Alexandrian trader announced. “Corbulo was the best of his generation!”

A crash from the far side of the room signaled the Roman’s attempt to stand. The stool had fallen backward as the man rose to his unsteady feet. He gestured to the girl, knocking the wine jug with his forearm. It smashed onto the floor.

The Roman swayed. His gaze found Crito’s and he pulled a handful of coins out of the leather pouch on his belt. He rained them down onto the table.

“That’s for the wine. That’s for the jug.”

Crito gaped. Those were silver coins the Roman was throwing around.

The Roman blinked at them. “And that’s for the stool.”

Crito moved out from behind the counter. “The stool, sir? The stool is fine.”

The girl hurried toward him. “Master, shhh! Let him. Let him.”

Let him? Let him what? Crito gasped as the Roman turned, stooped to pick up the stool, and swung it. He roared, and the stool shattered against the wall.

The Roman stood panting.

“No, no, no,” Crito babbled in the sudden silence, looking anxiously toward his other customers. “No, you must go outside, please.”

“Get me another drink,” the Roman said. He sat back at the table on the girl’s stool.

“Master,” the girl said, pulling Crito away by the wrist. “Do as he says.”

Crito looked at her, looked at the Roman, looked at the smashed stool and looked at the coins.

“You can serve him,” he growled, “as long as he keeps paying.”

“His money is good, master,” the girl said. “His goodwill is better.”

Crito snorted. He hadn’t seen much in the way of goodwill from the Roman so far. “Why is he so special? Didn’t you hear?” He raised his voice without intending to. “The only important man to step foot in Cenchreae today was Corbulo, and we killed him!”

The color drained from the girl’s face.

“You didn’t kill Corbulo,” the Roman said suddenly. His mouth quirked up in a bitter smile. “I did.”

“Y-you did?” Crito didn’t dare look at his other customers. They were all frozen to the spot.

A young man, Crito thought wildly. The Roman was a young man. He should have spotted it sooner. Despite the nondescript cloak and the standard military-issue gladius, the Roman was too young to be an ex-legionary, and a soldier on leave wouldn’t drink alone. His accent wasn’t just Roman, it was patrician. Crito should have recognized it sooner. The girl--clever girl!—had picked it up. This was a man Crito did not want to offend.

“I did,” the Roman said. “With nine little words.”

The girl was the only one unafraid to move. She placed a cup of wine on the Roman’s table.

Crito couldn’t break the man’s gaze. He didn’t want to ask, but the Roman was waiting for it. “Nine words?”

The Roman slid a coin across the table toward the girl. He drank, and wiped his mouth on the back of his hand. “He knew me. Ushered his daughter toward me. Mentioned my father’s name.”

Cold dread leeched into the pit of Crito’s gut. No, no, no. He did not want to hear this. He watched as the girl ran a thin hand along the Roman’s forearm and marveled at her audacity.

The Roman drank again. He looked around the wine shop at his captive audience. “Want to know the nine words it takes to kill a hero?”

Nobody spoke.

The Roman’s face cracked with a smile. “You no longer have the friendship of the emperor.”

One of the traders whispered something.

The Roman raised his eyebrows, his face suddenly animated, almost boyish in surprise. “And do you know what he said before he fell on his sword?”

A short, bitter laugh.

Crito stepped forward with a wine jug. His hands trembled as he poured the Roman another cup. “Axios,” he murmured.

He is worthy.

“Axios,” the Roman agreed. His smile faded. He traced his finger through a pool of spilled wine on the table, around the islands of coins, and admitted there, to a group of anonymous strangers in a nondescript wine shop, what Crito doubted he would even admit to himself if he were sober. “Well, maybe Nero’s not fucking worthy. Did anyone ever think of that?”

Chapter Two

The Aventine, Rome, June 68 A.D.

“Up! Up! Up!”

Aenor hauled himself to his feet and squinted into the sudden light. He understood the command, but not the burst of words that followed. Aenor’s Latin was good, he thought it was, but these men spoke too fast. He averted his gaze from the light of the lamp. Filthy twists of hair hung in front of his face.

One of the voices belonged to Ratface. Aenor didn’t know his real name. He was the overseer, thin but sinewy, with a narrow, pinched face and close-set eyes. He carried a whip and was quick to use it.

Aenor didn’t recognize the second voice, and risked a glance.

The man was tall, middle-aged, not handsome, but clean and maybe rich. His tunic was orange and he wore silver rings on his fingers.

“No,” the Clean Man said to Ratface. “I am not a fool.”

Fool? Infant? Aenor had to guess the word from the tone of the man’s voice. His uncle had insisted he learn Latin, and Aenor had thought he had, but there was so much he didn’t know. He knew enough to sell cloth and jewelry to fat wives in Colonia, enough to tell a legionary to fuck off back to Rome, but not enough for this.

Not enough for slavery.

The attack had come out of nowhere. Well, no, not nowhere. Someone had killed a Roman family traveling on the road. An important man, perhaps, and his woman and children. And Aenor and his cousins had laughed, because the man should have paid for better bodyguards, but it wasn’t him and his cousins who had done it. When the legionaries had stopped their carts, they weren’t expecting trouble. A bit of back-and-forth maybe, an insult, a bribe, that was all. They had realized too late to run that this was different. Aenor had been taken and Bana was dead, he’d seen that, but he didn’t know what had happened to the others.

“Filthy Bructeri scum,” the First Spear had said, his greaves covered with blood, and suddenly Aenor wasn’t a free man anymore.

Had it only been weeks? It felt like years he’d been living in this dark cage. He kept his head bowed and listened as Ratface tried to sell him. The dull ache in his stomach, he thought, was the empty place he used to keep his fear.

“I will give you a good price,” Ratface wheedled. Aenor had promised the same thing to those women who’d hummed and hawed over his bolts of woven cloth back in Colonia. “He is—” A sly, teasing word Aenor didn’t know.

The clean, rich man made a clicking noise with his tongue.

“And he will clean up nicely,” Ratface said.

Nicely? Well? Adequately? Aenor stared at his feet.

Aenor had been sold twice since being captured, beginning when the First Spear sold him to the trader for only four hundred denarii. The trader—Aenor had named him Squinteye—had bound Aenor behind his wagon and turned south.

Every sunset and every dawn, every blistering step, every passing moment had pulled Aenor farther away from home. Pulled him into the nightmare he couldn’t escape. The farther south they had traveled, the more different even the air smelled: alien combinations of salt, laurel, and bay trees. Even the dust smelled strange. How would he ever find his way home from here?

Aenor’s first sight of Rome had been a smudge of smoke haze above hills. Too vast to be a city, surely, and his confusion must have shown on his face because Squinteye had laughed and smacked him on the back of the head. Roma. That was Roma.

The road had become wide, busy, and was shadowed for some miles by a massive arched aqueduct. Aenor had seen small farms dotted with goats and sheep. He’d seen huts, ramshackle and packed closer and closer together. Then there were the tombs, some as large and spectacular as palaces, that lined the side of the road. Carved letters that Aenor couldn’t read spelled out the life achievements of the great Romans who reposed inside. All around the tombs, beggars and thieves slipped in and out of the shadows and kept their watchful eyes on the road.

The city itself--sacred Tuisto! Aenor had never seen anything so big, so busy, so loud. Squinteye had left his wagon outside the city with his biggest, most trusted men to guard it, and headed into Rome with Aenor and the rest.

Buildings as high as mountains. Some, Aenor saw, had five or more stories. So many people, so much noise, so much stink. Rome was so big. Too big.

Squinteye had sold him to a fat man who’d brought him to Ratface.

Ratface had put him in a locked cage with four other slaves, none of whom spoke even the rudimentary Latin that Aenor did, in a long, narrow warehouse full of similar cages. Ratface had put a rope around his neck with a tag on it, and threw food into the cage once a day.

As the newest occupant of the cage, Aenor had been given the space closest to the corner they all shat in. The first night, Aenor sat awake, his face buried in his hands, and thought about the goats and sheep he’d seen at the side of the road. Even animals didn’t have to shit where they ate.

By the second night, he was too numb to care.

The days and nights bled together into weeks, and now the Clean Man was here. Aenor told himself he wasn’t afraid, but his skin prickled under the man’s scrutiny, and his guts twisted. He kept his eyes on the ground and forced his trembling fingers straight. Slaves did not make fists.

“It’s a fair price,” Ratface said, “and this one will give you no trouble at all.”

Aenor closed his eyes and tried to imagine he was somewhere else.

The Clean Man clicked his tongue again and sighed. “I suppose he will do,” he said at last. “Send him with the rest.”

When they left, Aenor sank down onto his haunches. He couldn’t stop the acid trickle of fear in his guts. Not afraid, not afraid, but his body didn’t believe it. When he vomited in the corner of the cell, none of the others even looked at him.

*****

Aenor was chained up with five others he didn’t know. They were younger than him, just as filthy. One of them had darker skin than Aenor had ever seen. Rome was so vast, it straddled the world. So much bigger, so much stronger than Aenor had ever imagined when he’d laughed with his cousins back home about what they’d do to the Romans, about how the forest had once swallowed an entire legion. They were Bructeri. They were proud.

They were small. Powerless. Hopeless.

Aenor tried not to whimper as Ratface fastened his chains to the boy in front of him and led them outside.

The sunlight blinded him. Aenor lifted an arm to shield his eyes, and the heavy chains rattled. He walked into the boy in front of him before he realized he’d stopped. They knocked together like skittles, and Ratface laughed.

They walked. Aenor winced at the noise, at the light.

The boy in front of Aenor started to cry. He was small, with skin the color of pitch. He was repeating something over and over, a word Aenor did not know. A god, maybe, or perhaps a parent or a sibling.

No. Don’t.

Aenor watched his feet as he walked, and the feet of the boy in front of him. He stole glimpses of the sunlit world.

A road that crested a hill.

A bottleneck of pedestrian traffic in a large covered marketplace.

A red-roofed building with an arched colonnade.

Plastered walls covered in graffiti and slogans.

A temple.

Aenor stared wide-eyed at a sculpted god, and it stared back at him. The painted orbs of its eyes seemed to see nothing and everything. His head was adorned with garlands of wilting flowers. Aenor didn’t know the Roman gods, but he was afraid of them. He had pleaded with them before.

“Placet,” he had said over and over in the beginning. Please. Please. Please.

The Roman gods were deaf to him, then and now.

“Placet,” he murmured as he passed, but the god in the temple portico stared straight ahead.

Aenor’s muscles ached. The boy in front of him stumbled. Aenor tried to sidestep him, and was pulled back by the length of chain around his neck. He struggled to keep his balance, struggled not to cry out.

In front of him, the boy kept repeating his secret, sacred word.

Tears stung Aenor’s eyes. He wanted to reach out for the boy’s hand, but couldn’t.

Aenor looked up again as they passed through a gate into an arched passageway. A pair of soldiers closed the gate behind them.

“Here’s a fine litter of pups!” one of the soldiers called out, and they laughed.

“Too fine for you!” Ratface returned with a sneer.

After the sunlight and the bustle, it seemed cold and quiet in the passageway. The boy in front of Aenor sobbed as they were led farther into the darkness. Aenor’s guts twisted. What if the boy knew something he didn’t? What if this was the way to the arena? Aenor didn’t want to die for the sport of Romans. He didn’t want to die at all. He just wanted to go home.

Home. The thought was as sharp as a blade, and Aenor flinched.

No. That was never going to happen. He was a slave now. Maybe the Clean Man would be a kind master. Such men existed. Even in Castra Vetera, Aenor had seen fat, pampered slaves. He had heard of slaves who were freed by their masters. He had heard of ex-slaves who were rich. Perhaps being sold to the Clean Man was a good thing. It had to be better than Ratface’s cell.

Ratface led them out into the sunlight again. This time they were surrounded by fine buildings and gardens. Ratface led them toward one of the nearer buildings. A man waited for them at the door. The Clean Man.

The Clean Man glanced at the slaves, and then shook his head at Ratface. “Tell your master I expect better stock next time.”

Ratface sneered. “Tell your master to keep his hair on!”

He began to unchain the slaves.

Aenor kept his gaze down. The Clean Man was a slave. A clean slave. A well-dressed slave. Maybe their new master treated all his slaves so well.

Aenor rolled his shoulders as the weight of the chain slid off him. Hope, uncertain and shy, flared in his chest.

He had seen collared slaves before in Colonia. He had seen tattooed slaves as well, and branded slaves, their master’s initials burned into their faces. The Clean Man bore no marks that Aenor’s quick gaze could find, and wore no collar around his neck. Maybe it didn’t have to be bad. Maybe they wouldn’t make him feel like an animal.

The Clean Man opened the doors of the building, and a cloud of steam billowed out.

Aenor’s eyes widened as the Clean Man ushered them inside. A small group of slaves met them, stripped their ragged clothes from them, and set about them with coarse sponges and buckets of hot water. Aenor closed his eyes, embarrassed at the rivulets of dirty water that ran off his skin. He knelt when the man washing him put pressure on his shoulders. The man dunked his head in a steaming bucket. Aenor yelped at the heat, but the man held him there. When he finally released him, Aenor saw through the dripping tendrils of his hair that the water was now dark gray. He was filthy. He submitted patiently to the rest of the man’s ministrations, sitting quietly while the man took to the planes of his face with a gleaming razor and pumice stone.The man tugged Aenor’s hair over the edge of the razor, the ragged, wet locks dropping to the floor. When the man stepped away, Aenor raised a hand to his bare neck. His hair was shorter than he’d worn it since childhood. It curled around the nape of his neck. It felt strange.

“This one is done,” the man said.

The Clean Man looked him up and down, and clicked his tongue. “Hmmm. We will see. Send him to wait. Check him.”

Aenor, naked, was pushed toward another door.

He shivered.

Too many hands, too many people keeping him moving, too many different faces and places. The man who had washed him shot him a narrow look as they hurried along a passageway. “You understand me?”

“You talk slow, I understand,” Aenor said, anxious to obey.

Trade, he knew. Numbers and orders and prices, he knew. This, whatever this was, he didn’t know, and he was afraid of punishment.

“You follow,” the man said. “You do what I say.”

Aenor nodded.

“In here,” the man said, pulling Aenor into a small room.

Another man was already in there. The master? No. Aenor looked at the frayed hem of his tunic, at the scars across his knuckles. This was not a rich man.

“We check him,” the first man said.

The second man grinned slowly. He said something in an accent too thick for Aenor to understand. Except for that one word.

No. No. No.

The word was close enough. Fuck you! Aenor had screamed in Latin at the legionaries who’d captured him. Tete futue! He knew the obscenity well enough to recognize its conjugation even through the thick accent of the burly slave who was now advancing on him. And, even if he hadn’t, the big man leered and mimed the action.

He was going to be fucked.

No. Tuisto, no.

The big man grabbed him by the shoulders, turned him around, and pushed him down onto the floor. Aenor whimpered and struggled as the man behind him slid a thick finger into the crease of his ass. The second man, the one who had so carefully shaved his face, caught Aenor around the wrists and jerked him roughly forward. The man behind him kicked his legs apart and knelt between them.

Aenor choked on his own sobs. He tried to twist away, and the man behind him growled and reached down to grab his balls.

“You want move?” the man demanded in his strange accent. He tightened his grip. “You want move?”

Aenor whimpered and shook his head.

The man kept a firm grip on Aenor’s balls as his probing finger returned to the crease of his ass. Aenor sucked in a panicked breath as the man’s dry finger breached him. It stung. The man pushed his finger inside Aenor’s passage, muttered something, and pulled it out again.

He used the same word Ratface had to describe Aenor to the Clean Man back at the warehouse. This time, Aenor could hazard a guess: virgin. Ratface’s examination had never been quite so thorough, though.

The big man moved away.

The other man released his grip on Aenor’s wrists. “Up. Get up.”

Aenor, trembling, wasn’t sure his legs would hold him.

“Up!” the man barked.

Aenor struggled to his feet. He backed away from the men into the corner of the room, his gaze fixed on the floor, his hands held in front of his genitals. A shudder ran through him and he squeezed his eyes shut.

There was a place, a secret place that Aenor’s people knew, where the scattered helmets and spears of lost Roman legions moldered in the earth. Aenor had seen it. He had held a helmet in his hands, marveled at the weight of it, and spat on the bones of the man it came from. It was easy to hate Rome in the Teutoburg Forest. It was easy to feel strong.

Not here. Here he was weak. Here he was going to be bent over for Romans, fucked by them.

“And what do we have here?” came a voice from the entranceway. It was a rich man’s voice. A proper Roman accent. The master.

Aenor opened his eyes.

The man wore a long blue tunic shot through with silver threads. He wasn’t tall, but he was handsome. A patrician nose, lips inclined to thinness, and sharp eyes. His neatly cut hair was beginning to turn gray. He wore gold rings on his fingers.

“Do you have Latin?” the master asked him.

Aenor’s voice cracked in his throat. “S-some.”

The burly slave moved quickly. He slapped Aenor’s face. “Dominus.”

Aenor blinked away the sudden tears. “Some, Dominus.”

The master didn’t smile. “What are you?”

“Bructeri, Dominus.”

“German,” the master said. “How old are you?”

His voice shook. “Nineteen, Dominus.”

The master frowned. “Nineteen?” He raised his voice. “Callistus!”

Aenor shrank back.

The Clean Man appeared in the doorway. “Dominus?”

“This one is nineteen!”

The Clean Man gazed at Aenor for a moment. “He doesn’t look it, Dominus. And he’s a virgin.”

The burly slave nodded eagerly in agreement, and Aenor’s face burned.

“I’ll take him,” the master said. “But I expect better in the future.”

“Yes, Dominus,” the Clean Man said.

The master sighed, narrowing his eyes at Aenor. “And make him . . .” He waved his hand. “He’s too old for pretty. Make him look strong. He’s hardly a keeper, but I’m sure he can put on a good show.”

“Yes, Dominus.”

Aenor closed his eyes again.

There was a place . . . a clearing surrounded by trees. A place that still whispered of victory. A place where Aenor had held a Roman helmet in his grasp and laughed as hot blood had coursed through his veins. He was strong in that place.

He searched for it in his memory, invoked it by its secret name, but couldn’t find it. It was lost to him now.

It was Rome’s turn to laugh.