|

All he wants is the love he lost.

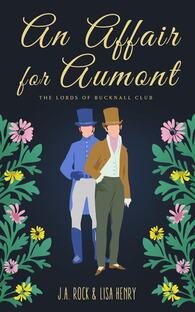

Four years ago, Louis-Charles Aumont, the Marquis de Montespan, chose duty over the man he loved. And then the man he loved chose death in service to England. Now, after finally cutting ties with his king, Aumont is living in a slum in Seven Dials–and intending to die there too. But when Bow Street Runner George Darling shows up at his door with a strange proposition, Aumont is intrigued by the prospect of something–anything–that might make him feel alive again. Or at least provide the funds he needs to drink himself to death. All he wants is the love he couldn’t have. George Darling joined the Bow Street Runners out of a belief in order. He accepts no bribes, indulges in no vices, and tries very hard not to dream above his station. If only Lord Christmas Gale hadn’t put that last one to such a test. Now that turning his thoughts from Lord Christmas only lands them instead on the handsome Frenchman with whom he recently crossed paths, Darling is more determined than ever to keep his head down and focus on his duty–until a knock on his door sends his life into disarray. Teddy Honeyfield, a former companion of Lord Christmas’s, is in need of a temporary bodyguard. Darling would never pass as the sort of gentleman Teddy requires…but he knows someone who might. Neither wants to take a chance on a love that can never be. When Aumont and Darling join forces to help Teddy, they’re not expecting to risk their hearts as well as their lives. Darling’s striking looks remind Aumont quite painfully of the man he’s lost, and Aumont’s title reminds Darling he has no right to desire a nobleman. But the rising threat soon drives them to flee with Teddy to the country–a journey that puts them face-to-face with their pasts while showing them a chance for happiness is within reach, if only they’re courageous enough to grab it. An Affair for Aumont is the fifth book in The Lords of Bucknall Club series, where the Regency meets m/m romance. The Lords of Bucknall Club can be read in any order. |

"This is my favorite of the series so far! Yes, it is a bit darker than the previous books in some ways, but I found both Aumont and Darling to be such compelling characters."

- Love Bytes

"I laughed my arse off where I was supposed to, I felt emotions of hurt and pain where I was supposed to, and I cheered for them throughout. All winning aspects for my personal reading pleasure."

- On Top Down Under Book Reviews

- Love Bytes

"I laughed my arse off where I was supposed to, I felt emotions of hurt and pain where I was supposed to, and I cheered for them throughout. All winning aspects for my personal reading pleasure."

- On Top Down Under Book Reviews

Buy An Affair for Aumont here:

https://books2read.com/Aumont

https://books2read.com/Aumont

An excerpt from An Affair for Aumont:

The woman hitched up her skirts, gripped the goose between her dimpled knees, and drew its long neck out straight with one hand. In her other hand she held a cleaver, which she raised—Aumont imagined sunlight catching on the blade, but the late afternoon was too cloudy for that—and then swung downward.

Thock.

The goose and its head were separated.

Aumont turned away, sour bile rising in his throat as he fought the urge to be sick. He pulled his coat tighter around him and stumbled down the street. He was drunk enough that he was having trouble walking, but nowhere near as drunk as he aspired to be, and Seven Dials, a hive of vice, disease, and crime, was the perfect location for a man with such an ambition. It was a warren, a slum, and for the past fortnight had been Aumont’s latest place of residence. He had every intention that it would be his last.

His unsteady gait carried him to the next street, and to a row of gin shops. He wheeled into the first and bought two bottles of gin, slid them into the handy panniers of his coat pockets, then swore at the man who attempted to liberate them as he turned to leave. The owner of the gin shop chased the man away with a broom, but Aumont remained vigilant as he continued on to his boarding house. It didn’t take much to make oneself a target in these narrow, stinking streets, and two full bottles of gin were as much bait to the denizens of the Dials as a bulging purse would be. Aumont was drunk, but he kept his somewhat fuzzy wits about him all the same.

His boarding house was in Little White Lion Street. It was a hovel, but Aumont had a private room where he could drink himself into a stupor so as not to hear his neighbours either fighting or fucking, or both, so what did he care if he was visited by rats? He threw empty bottles at them when he caught them scuttling along the filthy skirting boards, and they hadn’t yet bitten his fingers off while he lay passed out on the bed—though the bedbugs were doing their best to devour him.

He climbed the dark stairs, warily eyeing a woman coming down them. She warily eyed him back. When he reached his room, he unlocked the door to enter and then closed it again behind him. He lit a candle, and the stink of burning tallow filled the room. Then he sat down heavily on his filthy bed and opened his first bottle of gin.

He thought, as he always did, of France. His deep love of her. His deep hatred of her. The gin didn’t help him untangle those two things—it never did--but it got him drunk enough to stop caring that he couldn’t. He closed his eyes for a moment, which possibly extended for longer than he thought because, when he opened them again, the candle had burned down quite some way, and there was someone knocking on his door.

Aumont sneered at the door. If Toussaint had tracked him down, well, clearly Aumont hadn’t told him loudly enough the first time.

“Va te faire foutre!” he yelled at the door.

The knocking paused, and then a voice said, faintly, “Pardon?”

The door creaked open, and Aumont cursed himself for having forgotten to lock it. But it wasn’t Toussaint who stood there, ready to threaten or cajole Aumont back to sobriety and to the service of the King of France, but the Bow Street Runner who’d been dogging his footsteps ever since the mess with Soulden and the Craufords.

Darling, the Runner, was a young man with an open and honest face. He was about the same height as Aumont, but broader, with an easy, sturdy strength about him, and, from what Aumont remembered of their conversations, a countrified Kent accent that seemed entirely out of place in filthy, sprawling London. It made Aumont think of farm boys and fields and clean, fresh air.

Aumont swigged from his bottle. “You’re on the wrong side of the river, Mr. Darling.”

Darling took his hat off and held it in the crook of his elbow. The scant candlelight wasn’t enough to show that his eyes were blue, but Aumont remembered they were. He’d looked into them in Soulden’s house the night he’d killed Crauford, wanting a glimpse into the soul of the man who was going to arrest him. Wanting, perhaps, to imbue the moment with greater meaning, with the sort of spiritual weight that would give him something to ponder in a gaol cell while he waited to be hanged. But Darling hadn’t arrested him. He had simply escorted Aumont as far as Russell Square before releasing him. And Aumont had stood there, helplessly, with no idea how to explain to this fool that he needed to die, that he was too much of a coward to fling himself from a bridge into the Thames, and so he needed Darling to put him in front of a magistrate. But Darling had only nodded, then slipped back into the darkness of that foggy night, leaving Aumont to ponder whether the blue of the Runner’s eyes had matched the blue of the eyes in that portrait.

Luke’s portrait.

It had hung on the wall above Aumont when he’d killed Crauford. It was a good likeness, though not a perfect one—Luke was far too handsome, far too full of light to be captured in oils—but the eyes had been so right that Aumont had dreamed of Luke every night since, dreams that all the gin in the world couldn’t prevent from becoming nightmares. He almost wished that in his dreams Luke was something terrible and ugly, something decayed and grotesque, but no, he was the Luke that Aumont had loved—handsome and kind and clever and tender—and they made love, or held hands, or bickered about something inconsequential until they both surrendered to laughter. The nightmare came, as always, when Aumont awoke and his heart was torn out, every fucking time, by the realisation that Luke was dead.

“You’re on the wrong side of the river,” he said, and it took him a moment to remember he’d already said that, but Darling hadn’t yet responded. Well, if he wanted to be silent and mysterious, good luck to him. In the meantime, Aumont had gin to drink. He took another swig, amused at the expression of deep concern that crossed Darling’s face. “What are you doing here?”

“I was...” Darling looked down and appeared momentarily engrossed by his hat. Then he lifted his gaze again. “I was concerned for you, sir. It’s not an easy thing to kill a man.”

Aumont struggled to sit fully upright, and more or less failed. He slumped back against the wall, cradling his gin. Looked at this earnest-faced farm boy and snorted. “Have you ever done it?”

“No, sir.”

“Then how the hell would you know?” He took another gulp, and then remembered his manners and held out the bottle. “Want some?”

Darling stood rigid. “No, sir. I do not drink.”

“Ah,” Aumont told the sagging ceiling. “He does not drink, he does not kill, he probably does not even fuck. Mon Dieu, please send me someone more interesting than this—this potato.”

The woman hitched up her skirts, gripped the goose between her dimpled knees, and drew its long neck out straight with one hand. In her other hand she held a cleaver, which she raised—Aumont imagined sunlight catching on the blade, but the late afternoon was too cloudy for that—and then swung downward.

Thock.

The goose and its head were separated.

Aumont turned away, sour bile rising in his throat as he fought the urge to be sick. He pulled his coat tighter around him and stumbled down the street. He was drunk enough that he was having trouble walking, but nowhere near as drunk as he aspired to be, and Seven Dials, a hive of vice, disease, and crime, was the perfect location for a man with such an ambition. It was a warren, a slum, and for the past fortnight had been Aumont’s latest place of residence. He had every intention that it would be his last.

His unsteady gait carried him to the next street, and to a row of gin shops. He wheeled into the first and bought two bottles of gin, slid them into the handy panniers of his coat pockets, then swore at the man who attempted to liberate them as he turned to leave. The owner of the gin shop chased the man away with a broom, but Aumont remained vigilant as he continued on to his boarding house. It didn’t take much to make oneself a target in these narrow, stinking streets, and two full bottles of gin were as much bait to the denizens of the Dials as a bulging purse would be. Aumont was drunk, but he kept his somewhat fuzzy wits about him all the same.

His boarding house was in Little White Lion Street. It was a hovel, but Aumont had a private room where he could drink himself into a stupor so as not to hear his neighbours either fighting or fucking, or both, so what did he care if he was visited by rats? He threw empty bottles at them when he caught them scuttling along the filthy skirting boards, and they hadn’t yet bitten his fingers off while he lay passed out on the bed—though the bedbugs were doing their best to devour him.

He climbed the dark stairs, warily eyeing a woman coming down them. She warily eyed him back. When he reached his room, he unlocked the door to enter and then closed it again behind him. He lit a candle, and the stink of burning tallow filled the room. Then he sat down heavily on his filthy bed and opened his first bottle of gin.

He thought, as he always did, of France. His deep love of her. His deep hatred of her. The gin didn’t help him untangle those two things—it never did--but it got him drunk enough to stop caring that he couldn’t. He closed his eyes for a moment, which possibly extended for longer than he thought because, when he opened them again, the candle had burned down quite some way, and there was someone knocking on his door.

Aumont sneered at the door. If Toussaint had tracked him down, well, clearly Aumont hadn’t told him loudly enough the first time.

“Va te faire foutre!” he yelled at the door.

The knocking paused, and then a voice said, faintly, “Pardon?”

The door creaked open, and Aumont cursed himself for having forgotten to lock it. But it wasn’t Toussaint who stood there, ready to threaten or cajole Aumont back to sobriety and to the service of the King of France, but the Bow Street Runner who’d been dogging his footsteps ever since the mess with Soulden and the Craufords.

Darling, the Runner, was a young man with an open and honest face. He was about the same height as Aumont, but broader, with an easy, sturdy strength about him, and, from what Aumont remembered of their conversations, a countrified Kent accent that seemed entirely out of place in filthy, sprawling London. It made Aumont think of farm boys and fields and clean, fresh air.

Aumont swigged from his bottle. “You’re on the wrong side of the river, Mr. Darling.”

Darling took his hat off and held it in the crook of his elbow. The scant candlelight wasn’t enough to show that his eyes were blue, but Aumont remembered they were. He’d looked into them in Soulden’s house the night he’d killed Crauford, wanting a glimpse into the soul of the man who was going to arrest him. Wanting, perhaps, to imbue the moment with greater meaning, with the sort of spiritual weight that would give him something to ponder in a gaol cell while he waited to be hanged. But Darling hadn’t arrested him. He had simply escorted Aumont as far as Russell Square before releasing him. And Aumont had stood there, helplessly, with no idea how to explain to this fool that he needed to die, that he was too much of a coward to fling himself from a bridge into the Thames, and so he needed Darling to put him in front of a magistrate. But Darling had only nodded, then slipped back into the darkness of that foggy night, leaving Aumont to ponder whether the blue of the Runner’s eyes had matched the blue of the eyes in that portrait.

Luke’s portrait.

It had hung on the wall above Aumont when he’d killed Crauford. It was a good likeness, though not a perfect one—Luke was far too handsome, far too full of light to be captured in oils—but the eyes had been so right that Aumont had dreamed of Luke every night since, dreams that all the gin in the world couldn’t prevent from becoming nightmares. He almost wished that in his dreams Luke was something terrible and ugly, something decayed and grotesque, but no, he was the Luke that Aumont had loved—handsome and kind and clever and tender—and they made love, or held hands, or bickered about something inconsequential until they both surrendered to laughter. The nightmare came, as always, when Aumont awoke and his heart was torn out, every fucking time, by the realisation that Luke was dead.

“You’re on the wrong side of the river,” he said, and it took him a moment to remember he’d already said that, but Darling hadn’t yet responded. Well, if he wanted to be silent and mysterious, good luck to him. In the meantime, Aumont had gin to drink. He took another swig, amused at the expression of deep concern that crossed Darling’s face. “What are you doing here?”

“I was...” Darling looked down and appeared momentarily engrossed by his hat. Then he lifted his gaze again. “I was concerned for you, sir. It’s not an easy thing to kill a man.”

Aumont struggled to sit fully upright, and more or less failed. He slumped back against the wall, cradling his gin. Looked at this earnest-faced farm boy and snorted. “Have you ever done it?”

“No, sir.”

“Then how the hell would you know?” He took another gulp, and then remembered his manners and held out the bottle. “Want some?”

Darling stood rigid. “No, sir. I do not drink.”

“Ah,” Aumont told the sagging ceiling. “He does not drink, he does not kill, he probably does not even fuck. Mon Dieu, please send me someone more interesting than this—this potato.”